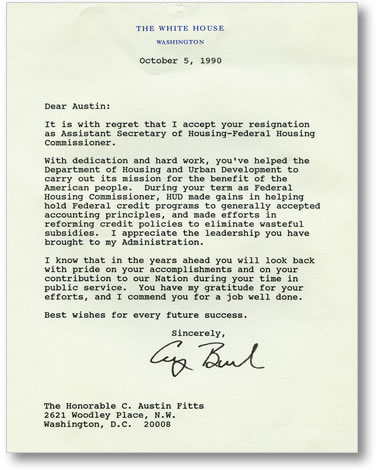

As Assistant Secretary for Housing-Federal Housing Commissioner, I was responsible for the operations of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which was the largest mortgage insurance fund in the world. FHA at that time had annual originations of $50-100 billion of mortgage insurance and an outstanding portfolio of $320 billion of mortgage insurance, mortgages and properties. Leading the FHA necessitated significant understanding of how homes are built, how mortgages finance thousands of communities throughout America and how investors finance the process by buying securities in pools of mortgages. My responsibilities included the production and management of assisted private housing; management of an organization of 7,000 employees in 80 offices nationwide; and development of network information systems and tools. In addition, I served as advisor to the Secretary of HUD on financial markets regulatory responsibilities, including the RTC Oversight Board, Federal Housing Finance Board and Home Loan Bank Board System, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

C. Austin Fitts, Assistant Housing Secretary, conferring with assistants during a break in her testimony before a Senate subcommittee. She was seeking higher limits on Government-backed loans. From left, Russ Davis, Peter Monroe, and Steve Britt. (The New York Times / Andrea Mohin)

When I told Nick Brady in 1989 that I was going to work at HUD, he said, “You can’t go to HUD — HUD is a sewer.” While my experience as Assistant Secretary cleaning up significant mortgage fraud that lost the government billions during the 1980s confirmed that HUD’s financial reputation was deserved, leading the FHA provided invaluable insight into how government management of the economy one neighborhood at a time really harms communities. Hence, access to the “real deal” on real estate and the mortgage markets was an opportunity. If you want to see the real economy in a place, you absolutely want an accurate map of the financial flows in that system — starting with the land and real estate. My favorite description of HUD was to come many years later from staff to the Chairman of the Senate HUD appropriation subcommittee — Senator Kit Bond. When asked what was going on at HUD, the Congressional staffer said, “HUD is being run as a criminal enterprise.” [29]

Catherine Austin Fitts being sworn in as Assistant Secretary of Housing in April 1989 by Jack Kemp, the Secretary of HUD. Catherine’s childhood friend, Georgie LaRue, is holding the Bible. (Photo courtesy Catherine Austin Fitts)

Shortly after arriving at HUD in April 1989, I began to learn about the FHA Coinsurance program. Since 1984, HUD/FHA had allowed private mortgage bankers to issue federal credit to guarantee multi-family apartment projects. After issuing $9 billion in mortgage guarantees, HUD/FHA was to lose something approaching 50% of the value of the portfolio — a level of losses hard to explain with mortal logic. When my staff approached me with a proposal to bail out a mortgage company so they could continue to lose money for us, I asked why we should spend money to lose more money in a way that would harm communities. After a long silence during which 30 staff members intently studied their feet, one brave soul explained to me that the mortgage bank was owned and run by a major Republican donor. Shocked, I said. “I am a major Republican donor,” and pointing to my presidential cufflinks that were adorning my French cuffs, “I got a pair of cuff links. You get cuff links. You don’t get $400 million of federal credit to throw down the drain.” My staff looked at me like I was so naive and clueless that there was no point in trying to communicate with me — better to let me learn the hard way.

Within minutes, a screaming Jack Kemp, furious that I had not provided illegal subsidy to keep the mortgage banking company going (despite his orders to stop anything corrupt or illegal), called me on the carpet. [30] The problems were compounded by the opinion of HUD General Counsel Frank Keating, who had joined from DOJ, that we did not have to honor our contracts. Rather we could abrogate contracts and ignore the law. If those who had been harmed sued us, Frank said, by the time they won “we will be gone.” Frank was to help write and pass new laws and administrative policies to use HUD as a source of War on Drugs activities and enforcement revenues. After many dirty tricks and much ranting and raving, HUD was to turn the defaulted coinsurance portfolio over to a private contractor named Ervin & Associates, a newly created company founded by John Ervin, a former employee of Harvard’s HUD property management company, NHP.

In the process of cleaning up the coinsurance portfolio, I got a chance to learn more about some of the tax-exempt housing bond deals that involved FHA mortgage insurance. Examples of these deals were those done through one of the Connecticut state housing authorities by a Dillon Read banker, Jewelle Bickford, during the 1980s. Bickford had a lot of support from two of the largest future Dillon Read investors in Cornell Corrections — Ken Schmidt and Birkelund — which was hard for me to fathom. Bickford was one for shortcuts and what sounded to me like more than little white lies. Schmidt shared an intelligence background with Birkelund. He served with Air Force Intelligence early in his career as Birkelund had served in the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI). When I later realized the role of the intelligence agencies in the HUD portfolio their comfort with HUD deals in Connecticut with high default rates seemed somehow more logical.

After Bickford’s housing bonds were embroiled in the coinsurance crash and burn, Jewelle somehow managed to get promoted up — landing at Birkelund’s old firm, Rothschild Inc. Which always made me wonder exactly whose bank accounts ended up with the $4 billion emptied out of the FHA mutual funds at HUD as a result of coinsurance, not to mention the billions more lost in the single family FHA programs. Over $2 billion was lost by FHA/HUD in the Texas region in fiscal 1989 alone. The Texas region had included Arkansas, where the state agency, ADFA was so bad they had been disqualified at one point according to the HUD Fort Worth regional leadership. It was this state agency which was alleged to have laundered the local profit share of the arms and drug trafficking channeled through Mena, Arkansas. [31]

For comparisons sake, $4 billion is about the amount of money that would buy you a controlling lead position in taking over one of the world’s premiere money laundering networks. When KKR raised the war chest in 1987 that gave them the wherewithal to bid and win RJR Nabisco, it amounted to $5.6 billion.

Money is like the Pillsbury Doughboy. When you squeeze down on one part, it pops up someplace else.

Wall Street Lessons: Dillon Read’s James Forrestal

James Forrestal’s oil portrait always hung prominently in one of the private Dillon Read dining rooms for the eleven years that I worked at the firm. Forrestal, a highly regarded Dillon partner and President of the firm, had gone to Washington, D.C. in 1940 to lead the Navy during WWII and then played a critical role in creating the National Security Act of 1947. He then became Secretary of War (later termed Secretary of Defense) in September 1947 and served until March 28, 1949. Given the central banking-warfare investment model that rules our planet, it was appropriate that Dillon partners at various times lead both the Treasury Department and the Defense Department.

Shortly after resigning from government, Forrestal died falling out of a window of the Bethesda Naval Hospital outside of Washington, D.C. on May 22, 1949. There is some controversy around the official explanation of his death — ruled a suicide. Some insist he had a nervous breakdown. Some say that he was opposed to the creation of the state of Israel. Others say that he argued for transparency and accountability in government, and against the provisions instituted at this time to create a secret “black budget.” [32] He lost and was pretty upset about it — and the loss was a violent one. Since the professional killers who operate inside the Washington beltway have numerous techniques to get perfectly sane people to kill themselves, I am not sure it makes a big difference.

Approximately a month later, the CIA Act of 1949 was passed. The Act created the CIA and endowed it with the statutory authority that became one of the chief components of financing the “black” budget — the power to claw monies from other agencies for the benefit of secretly funding the intelligence communities and their corporate contractors. This was to turn out to be a devastating development for the forces of transparency, without which there can be no rule of law, free markets or democracy.

I studied Forrestal’s oil painting with his solemn stare during many a private lunch — each time reminded that government service was an important duty and honor in the Dillon tradition but it was a dangerous business. Congressional Committees had roughed up Clarence Dillon. Forrestal had died. Douglas Dillon was Secretary of the Treasury when Kennedy was assassinated.

Because I wanted to understand how the world really worked, I listened carefully. Over years of private lunches and dinners and conversations I watched and listened to hundreds of lessons on how to be careful — the tricks of predator evasion in Wall Street and Washington. In the midst of many knowledgeable teachers, Forrestal’s leadership was a guiding light that was to serve me well in the years ahead.

Wall Street Lessons: The Power of the People

Another thing I learned on Wall Street is the extent to which those who appear to have little material power can have significant power when they organize to do so. My rise to partnership at Dillon Read was fueled by a steady stream of intelligence from loyal secretaries, print shop personnel, drivers and staff whose generosity, street smarts and hard work was a constant reminder that the rise to Wall Street’s board rooms was not necessarily based on performance as opposed to privilege. One of the greatest challenges as an associate at Dillon Read was knowing where to invest our time when multiple partners were pressing us to give priorities to their projects. Hence, a heads up from someone’s secretary that they were trashing me in the year-end reviews was insider intelligence worth its weight in gold. Giving first priority to those who supported us in year-end reviews and compensation could be the difference between failure and success.

Right after I became a partner, I got a call from a personnel department director who was looking for a new secretary for me. The person who called said they were interviewing someone who has been with a Canadian Broadcasting office in New York for seventeen years. This was her first interview since they shut the office down. She was absolutely excellent and if we wanted to recruit her we needed to make her an offer right away. The personnel director said, “The only problem is that she is Jamaican (of African descent), but she is very light skinned.” I was stunned and said something to the effect of “Who cares?” The personnel person said, “If I sent a black person to be interviewed with most of the partners in this firm, I would be fired.” And so I hired Pat Phillips to work for me and was the beneficiary of her extraordinarily overqualified talent until her death twelve years later, by which time she was a Hamilton shareholder and Secretary of our board.

Many years later, after I had started my own investment bank in Washington, D.C., I got a call from a driver at one of the car services that we used to use when I was at Dillon. He said, “Are you doing a deal with Ken Schmidt?” I explained that, yes, I had proposed working together on a fairly large complex transaction. It would take a lot of work but if successful would be great business for both firms. The driver said, “He was in the car last night. He was bragging about how he was going to screw you. Here is what he is going to do.” This was the same Ken Schmidt who had confessed the Dillon partners conversations with my ex-husband. Ken was still blubbering indiscreetly about his bad deeds. And so the driver saved me from my mistake of attempting to partner with my old firm.

| Next Chapter |