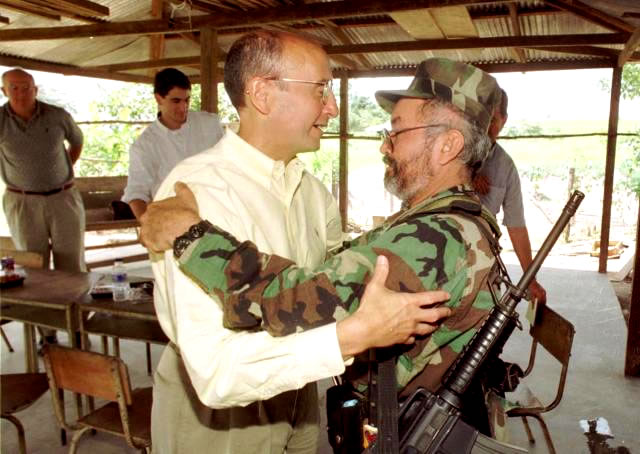

Photo: Richard Grasso (chairman and chief executive of the New York Stock Exchange from 1995 to 2003) hugging a FARC Commander in 1999 in a rebel village in Colombia. At this time, the GAO reported that FARC had assumed control of a majority market share of the Colombian cocaine trade.

(Photo courtesy LaRouche Campaign)

The Hamilton Securities Group had a subsidiary charged with taking our data as it developed on individual transactions and portfolio strategy assignments and using it to develop a new approach to investment. We sought to help investors understand the impact of their investments on people and places and on a wider society as a strategy to identify opportunities to lower risks and enhance investment returns.[83]This included understanding how to reduce the dependencies of municipalities and small business and farming on debt and increase their ability to finance with equity. Indeed, easy, subsidized access to equity financing is one of the reasons that large companies have grown so powerful and taken over so much market share from small businesses. Access to equity investment for small business and farms would result in a much healthier economy and much more broad-based support for democratic institutions.

We were blessed with an advisory board of very capable and committed pension fund leaders. In April 1997, we had an advisory board meeting at Safeguard Scientifics where the board chair led a venture capital effort. I gave a presentation on the extraordinary waste in the federal budget. As an example, we demonstrated why we estimated that the prior year’s federal investment in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania area had a negative return on investment. It was, however, possible to finance places with private equity and then reengineer the government investment to a positive return and, as a result, generate significant capital gains. Hence, it was possible to use U.S. pension funds to increase retirees’ retirement security significantly by investing in American communities, small business and farms — all in a manner that would reduce debt and improve skills and job creation. This was important as one of the chief financial concerns in America at that time was ensuring that our retirement plans performed financially to a standard that would meet the needs of beneficiaries and retirees. It was also critical to reduce debt and create new jobs as we continued to move manufacturing and other employment abroad. If not, we would be using our workforce’s retirement savings to finance moving their jobs and their children’s jobs abroad.

The response from the pension fund investors was quite positive until the President of the CalPers pension fund — the largest in the country — said, “You don’t understand. It’s too late. They have given up on the country. They are moving all the money out in the fall (of 1997). They are moving it to Asia.” He did not say who “they” were but did indicate that it was urgent that I see Nick Brady — as if our data that indicated that there was hope for the country might make a difference. I thought at the time that he meant that the pension funds and other institutional investors would be shifting a much higher portion of their investment portfolios to emerging markets. I was naive. He was referring to something much more significant.

The federal fiscal year starts on October 1st of each year. Typically the appropriation committees in the House and Senate vote out their recommendations during the summer. When they return from vacation after Labor Day, the various committees reconcile and a final bill is passed in September. Reconciling all the various issues is a bit like pushing a pig through a snake. Finalizing the budget each fall can make for a tense time. When the new bill goes into effect, new policies start to emerge as the money to back them starts to flow. October 1st is always a time of new shifts and beginnings. In October 1997, the federal fiscal year started. It was the beginning of at least $4 trillion going missing from federal government agency accounts between October 1997 and September 2001. The lion’s share of the missing money disappeared from the Department of Defense accounts. HUD also had significant amounts missing. According to HUD OIG reports, HUD had “undocumentable adjustments” of $17 billion in fiscal year 1998, and $59 billion in 1999. The HUD OIG refused to finalize audited financial statements in fiscal year 1999, refused to find out the basis of the undocumentable adjustments or to get the money back and refused to disclose the amount of undocumentable adjustments in subsequent fiscal years.[84] The HUD OIG continued to invest significant resources in persecuting Hamilton during this time.

Courtesy: New Yorker Magazine

The contractor who was blamed for the missing money at HUD was a financial software company named AMS. My old partner, Steve Fenster, the Dillon Read banker who led the firms effort in the Campeau leveraged buyout of the Federated Department Stores which had gone bankrupt (See my description expressing my concerns to Steve regarding this deal in “A Parting of the Ways” earlier in this story), had been a board member of AMS until his death in 1995, when he was replaced by Walker Lewis, a board member affiliated with Dillon Read and now, as Chairman of Devon Value Advisors, a consulting partner to Pug Winokur and Capricorn Holdings. With $17 billion and $59 billion missing from HUD, Secretary Cuomo never fired AMS or seized their money. Indeed the AMS Chairman Charles Rossotti was appointed IRS Commissioner and given a special waiver to keep his AMS stock. As a result, he profited personally when HUD kept AMS on its contractor payroll and new task orders were awarded to AMS by the IRS. As IRS Commissioner, he oversaw the responsibilities of the IRS criminal investigation division that plays a special role with respect to money laundering enforcement during the period when $4 trillion went missing from the Federal government. When Rossotti left government service, he joined Lou Gerstner at The Carlyle Group.

If we assume that the $17 billion went missing at HUD during 1998 on an even basis — that is, $1.4 billion a month, $63.6 million per week day, $7.9 million per working hour — by the summer of 1998, approximately $14 billion would have been missing from HUD alone, not counting other agencies. Where did it go? Was it financed with securities fraud using Ginnie Mae or other mortgage securities fraud or fraudulently issued U.S. Treasury securities? These are important questions. Interestingly, this was also a period in which some of the most powerful firms in Washington, D.C. or with Washington ties were having remarkably good luck raising capital. Indeed, the period of missing money coincided, not surprisingly with a “pump and dump” of the U.S. stock market and a significant flow of money into private investors hands.

Pump and Dump

Adapted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The financial fraud known as “pump and dump” involves artificially inflating the price of a stock or other security through promotion, in order to sell at the inflated price. This practice is illegal under securities law, yet it is particularly common.

Let’s look at some examples. Cornell Corrections was far from the only company to raise funds during this period and Dillon Read far from the only investor to cash out. Indeed, in the scheme of things, Dillon Read’s investment in Cornell Corrections can be described as a financially modest in size — albeit highly successful in percentage terms — venture investment. For example, Dillon’s investment and profits look tiny when compared to the billions that KKR was investing in RJR. Whether large or small, I would argue that both investments are highly informative regarding the real corporate business model prevailing in the US and globally.

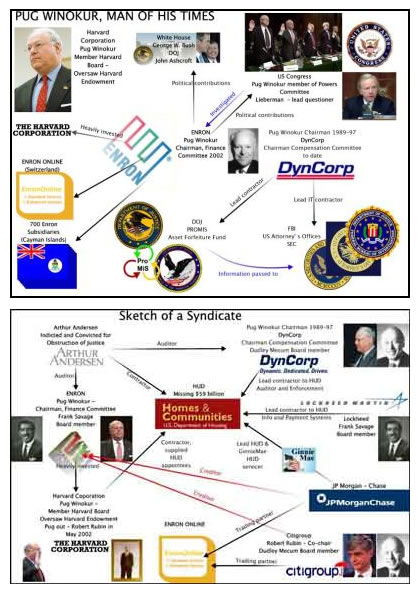

In the summer of 1998, Carlyle Group announced that it had closed its European Fund with $1.1 billion. By the end of the decade Carlyle had more than a dozen funds with close to $10 billion under management. In the meantime Enron, transacting with Wall Street, was enjoying a rush of good luck with offshore partnerships and growing revenues from “the new economy.” Enron’s leaders included a “Who’s Who” of government contracting. Pug Winokur was the chairman of the Enron finance committee. Pug was also an investor and board member in DynCorp, who was running critical and highly sensitive information systems for DOJ, HUD, HUD OIG and the SEC. Arthur Anderson, Enron & DynCorp’s auditor, (also Cornell Correction’s auditor) was a major contractor at HUD. Frank Savage, a board member of Lockheed Martin, the largest defense contractor that at the time was paid more than $150 million a year to run the HUD information systems, was also on Enron’s board and finance committee. Enron and HUD shared all the same big banks — Citibank, JP Morgan-Chase — and Wall Street firms. Winokur was on the board and invested with the Harvard endowment, a large investor in Enron. The attorney representing his firm on SEC documents, O’Melveny and Myers, a prominent Los Angeles firm, was reported to be the lead firm helping Al Gore during the 2000 election. Harvard University was a HUD contractor and major source of HUD, Treasury and White House officials. The Harvard Endowment was a major investor in HUD real estate and mortgage operations along with Pug Winokur and his investment company. Harvard employees were one of the largest groups of lifetime contributors to Bill Clinton. Harvard was also a source of appointees for OMB, DOJ, SEC, DOD and other agencies throughout the government.[85] During the Clinton Administration the Harvard Endowment rose from approximately $4 billion to almost $20 billion, an astounding performance.

Graphics by Sanders Research Group, republished from Scoop Media

To repeat a critical point made earlier in our initial discussion of the leveraged buyout business that has engineered a takeover of America’s economy — money is like the Pillsbury Doughboy. When you squeeze down on one part — it pops up someplace else. While we do not yet know the truth of who now has $4 trillion (or some other very large actual amount of cash and/or fraudulently issued securities) of undocumentable transactions indicating extraordinary amounts missing from the U.S. government or trillions more that disappeared out of pension funds and retail investors stock holdings during this period, we do know who has growing financial resources. We also know the extent to which extraordinary enforcement resources were used to target many of the honest people.

Sanders Research highly recommended ‘Mr. Global’ comic strip by Justin Ward and Chris Sanders:

On December 18, 1997, the CIA Inspector General delivered Volume I of their report to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence regarding charges that the CIA was complicit in narcotics trafficking in South Central Los Angeles. Washington, D.C. ’s response was compatible with attracting the continued flow of an estimated $500 billion–$1 trillion a year of money laundering into the U.S. financial system. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan in January 1998 visited Los Angeles with Congresswoman Maxine Waters — who had been a vocal critic of the government’s involvement in narcotics trafficking — with news reports that he had pledged billions to come to her district. In February Al Gore announced that Water’s district in Los Angeles had been awarded Empowerment Zone status by HUD (under Secretary Cuomo’s leadership) and made eligible for $300 million in federal grants and tax benefits. At the same time, the existence of Hamilton’s software tools and databases would have posed a significant risk if my team and I had become aware of the “Dark Alliance” story. The fastest way to connect the dots would have been for me and my teammates to have looked at the maps of high HUD single family defaults contiguous to areas of significant narcotics trafficking that we had posted on the Internet and then use the Hamilton Securities software tools and databases to dig deeply into government financial flows in the same areas, including patterns of potential mortgage and mortgage securities fraud.

The Map of South Central Los Angeles, California

(Map courtesy The Hamilton Securities Group)

The destruction, suppression and theft of our software tools, databases and computer system was arranged by a series of events between late 1997 and early 1998 that was so orchestrated throughout government, media and members of the Council of Foreign Relations that I would never have believed it if I had not lived through it.[86] The Washington Post mysteriously killed a story about what was happening to The Hamilton Securities Group at the last minute — just as they had done with the Mena story in 1995. Our errors and omission insurance carrier suddenly refused to pay our attorneys, who withdrew from representation of The Hamilton Securities Group.

Hayes Farm, purchased by Catherine’s maternal grandparents on their honeymoon and passed down through the generations, has a panoramic view of Mt. Washington and the Presidential Range in the White Mountains of New Hampshire — but no electricity. (Photos courtesy Catherine Austin Fitts)

I sold my interest in our family farmland to my uncle to try to get new attorneys to manage the assault of legal and investigatory workflow coming our way. The HUD OIG then called my uncle, apparently trying to persuade him that I was a criminal, and sent four HUD OIG and FBI agents to his home in New Hampshire at night with a subpoena. Their pretext was that they needed to review the family financial records for the farm to see if I had been entertaining government employees at this “vacation resort.” In time they would come to understand that no government officials had ever joined me at the farm and that the farm did not have electricity and depended on an outhouse for “basic” functions.

Judge Sporkin ruled against us in our efforts to get HUD to pay us immediately monies owed for work performed and then, for no legitimate reason, authorized our digital records and papers to be seized. On March 8, 1998, a court representative with a team of HUD OIG and FBI investigators landed in our offices and took them over. All copies of all documents whether in our office or in our homes and personal possessions were turned over. We were not allowed to keep copies of anything. We had been ordered by HUD to wipe all HUD databases from our server — most of which were available to the public by law — and certify that they had been wiped clean. We were told we could get copies or excess items of what had been turned over back quickly. In fact, with the exception of one server and a few computers, it took many years to recover any of our files. By the time our most critical files were returned to our control, our most valuable software tools had “disappeared” while under court control.

We were later to discover that DOJ was using CACI as a litigation support contractor on our case. CACI was the leading supplier of Geographic Information Systems software and services to the U.S. government who later was in the headlines as a result of their connections to the prison at Abu Grahbi in Iraq. This begs the question whether DOJ was paying our competitor to help themselves to our proprietary software and databases. Some time after our entire digital infrastructure was taken over, DOJ came out with a geographic information systems mapping tool to help support increased community policing and enforcement product. You had to wonder if this was the “Sheriff of Nottingham’s” answer to Community Wizard — rather than using software to allow citizens to understand what government was doing, why not use software to provide increased surveillance of citizens by government.

While in possession of our offices, the HUD OIG investigators took empty shredding bins, filled them up with trash and then — from a separate floor — found and added corporate accounting files and then staged photo-taking by the HUD IG General Counsel, Judith Hetherton, who then sent us a letter alleging obstruction of justice as evidenced by our “throwing out” corporate accounting records. We were saved by a property manager who witnessed this charade and decided to help us out after he saw the intentional — and very disgusting — trashing of the The Hamilton Securities Group offices and was touched by our efforts to clean it up. The property manager had come to the U.S. from Latin America—presumably to find freedom from lawless government. One of our attorneys went into the office when the federal investigators were there and came out shaking. He said to me, “My parents left Germany to get away from these people. Now they are here. Where do I go?”

Meanwhile, as soon as The Hamilton Securities Group’s digital and paper records and tools were under court control, computers auctioned off and websites taken down, Congress held surprise hearings on March 16, 1998 on Volume I of the CIA Inspector General’s Report on Gary Webb’s “Dark Alliance” allegations about government involvement in cocaine trafficking. The CIA Inspector General during these hearings disclosed the existence of the Memorandum of Understanding between the CIA and DOJ that had been created in 1982. Sporkin, the judge who had just engineered the destruction of Community Wizard and our digital infrastructure and had the carcass under his control, was the CIA General Counsel when that MOU was engineered.

There was one small glitch. When we were next allowed in our offices one evening in mid-March, we took the main server and brought it back to my home. The next day, a HUD auditor was stunned to see it gone — he assumed that everything would be wiped clean and sold. He asked where the server was and one of my partners said, “we took it last night.” At which point the HUD auditor said, “You can’t do that. My instructions are you are not allowed to have any of the knowledge.” He then could not come up with a rational reason or lawful basis as to why that was so and why The Hamilton Securities Group was to be denied access to its own property.

While the private prison companies were booking more contracts and billions of dollars were going missing from HUD, I spent the next months slugging through hundred-hour work weeks managing some eighteen audits, investigations and inquiries and twelve different tracks of litigation while struggling under the drain of significant physical harassment and surveillance and an ongoing smear campaign.

Information was dribbling out which ultimately would provide relief. Congresswoman Waters read the Memorandum of Understanding between the CIA and DOJ into the Congressional Record in May. Then in June, Gary Webb published his book Dark Alliance. I saw a brief piece pooh-poohing it in a corporate magazine and realized that somehow this might help explain the insanity that I was dealing with and could not understand.

After reading Dark Alliance, I started to study the extraordinary moneymaking business that DOJ and agencies like HUD had built in enforcement that really only made sense if in fact the government was entirely complicit in narcotics trafficking and related mortgage and mortgage securities fraud. I started to realize the extent to which private information systems and accounting software companies like DynCorp and AMS were taking control of government agencies behind the scenes — thus creating the conditions for billions of dollars to disappear from government accounts. Then I started to research private prison companies when a banker from our bank — whose colleagues’ behavior had been egregious and I believe criminal towards us—told me how much money they were making in Washington D.C. gentrification and private prisons. This was a theme that kept repeating itself during this period. Private prisons were the next “big thing” and were going to be “real money makers.” It was not just Scott Nordheimer who had tried to persuade us of this. When I had met with several senior partners of Coopers & Lybrand in late 1994, they assured me that I should shift my focus from communities to prisons — that the future was in enforcement and prisons.

In September, I discovered that DOJ owned a prison business company, the Federal Prison Industries, marketed by the name of UniCor. It markets federal prison labor to federal agencies. It turns out that Edgewood Technology Services, a Hamilton Securities Group brainchild and investment, was a potential competitor with DOJ’s own prison company for federal data servicing contracts. UniCor’s website indicated that they had a growing data servicing business with a focus on Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software products — the same as Edgewood Technology Services. It made me wonder if Scott Nordheimer had given DOJ and its Federal Bureau of Prisons our business plan despite my insistence that we were not interested in prison opportunities. I called the head of the data-servicing group in UniCor, who was amazed to hear the story I told him. He said something to the effect of: “That makes no sense. Most people end up in prison because they cannot get good jobs. It is much more expensive to have them working in prison than not come here in the first place.” He was eager to meet with me, as he was interested in helping good data servicing workers find jobs when they left prison. I told him to check with his superiors and that I would love to meet with him. He never called me back.

Federal Prison Industries

The Department of Justice’s profits from prison labor grew along with the growth of federal prisoners — the vast majority of whom were non-violent offenders. An April 12, 2004 story in Government Executive magazine, Prison labor program under fire by lawmakers, private industry, by K. Daniel Glover shows the rise of DOJ’s prison sales and labor force as more arrests and incarcerations are good for business.

Federal Prison Industries’ Growth

|

Year

|

Number of Factories

|

Sales (Millions)

|

FPI Workers

|

Total Inmates

|

Product Groups

|

| 1985 | 71 | $238.9 | 9,995 | 36,042 | 4 |

| 1990 | 80 | 343.2 | 13,724 | 57,331 | 5 |

| 1995 | 97 | 459.1 | 16,780 | 90,159 | 5 |

| 2000 | 105 | 546.3 | 21,688 | 128,122 | 5 |

| 2001 | 106 | 583.5 | 22,560 | 156,572 | 8 |

| 2002 | 111 | 678.7 | 21,778 | 163,436 | 8 |

| 2003 | 100 | 666.8 | 20,274 | 172,785 | 8 |

Source: Federal Bureau of Prisons, quoted at http://www.govexec.com/dailyfed/0404/041204nj1.htm

A report from The Center for Public Integrity in September 2004 reported that the Federal Prison Industries was the 72nd largest defense contractor with $1.4 billion of contracts between 1998-03, describing it as follows:

“Federal Prison Industries, also known as UNICOR, uses federal prisoners to manufacture a wide variety of products including furniture, clothes and electronic equipment. It also provides administrative services such as data entry and bulk mailing. A government-owned corporation, it operates as a part of the Federal Bureau of Prisons and is the Defense Department’s number one supplier of clothing, furniture, and household furnishings.”

Then on October 8th, an hour after the House of Representatives voted to move forward with the Clinton impeachment hearings, the CIA quietly posted Volume II of the CIA Inspector General report on the “Dark Alliance” allegations on their website. Volume II included a copy of the Memorandum of Understanding between DOJ and CIA. The message from President Clinton to the Republicans was simple and clear. “You take me down and I will take everyone down.” Literally the next day, October 9th, Secretary Andrew Cuomo issued a series of sole source contracts through Ginnie Mae, the mortgage securities operation at HUD, to John Ervin’s company (the same company leading the qui tam lawsuit against Hamilton) and to Touchstone Financial Group, a firm apparently started by a former Hamilton Securities Group employee who brought on a series of former Hamilton people to do some of the Hamilton work for HUD. One can only make a list of more unanswered questions of the political deals that may have been happening behind the scenes. After all, October 1, 1998 was the beginning of the fiscal year in which HUD was missing $59 billion from its accounts — for which the HUD OIG was to refuse to provide an audit as required by law. This amount of money translates into $4.9 billion per month, $1.2 billion per work week or $30.7 million per work hour. This was somebody’s payback time.

A FOIA response by HUD indicated that HUD Secretary Andrew Cuomo had engineered Ginnie Mae contracts for Ervin in October 1998 that could help finance Ervin’s lawsuits against HUD and Hamilton Securities.

Disgusted with events in Washington during this period, I headed to New York to try to get a sense of what this meant on Wall Street. I went down to Wall Street to have lunch with Bart Friedman, one of the partners at Cahill Gordon, Dillon Read’s lead law firm. Bart was someone I had immense respect for and who had helped Hamilton with our legal work. As we were having lunch at a private club near Cahill, Bart’s senior partner, Ike Kohn, walked by. When I was at Dillon Read, Nick Brady would introduce Ike as our most trusted attorney. Bart said something to the effect of, “Ike, you remember Austin Fitts.” Ike looked at me and sneered with hostility and walked away abruptly in a manner that was shocking to me. At least it was shocking until I saw the SEC filings for Cornell Corrections. Bart Friedman had handled all of Dillon’s investment and underwriting files for Cornell Corrections. While Ike may have been scared that I might connect the dots at lunch, I did not. I plowed through the SEC documents for Wackenhut Corrections and Corrections Corporation of America. I did not look at Cornell until years later. To this day I wonder what Ike knew about what happened to The Hamilton Securities Group.

It’s a Small World: While Cahill Gordon & Reindel was helping Dillon Read build Cornell Corrections, it was also providing legal counsel to The Hamilton Securities Group.

I then headed to a birthday party for a member of the family of a Dillon Read partner being held at the Colony Club, an elegant private club on Park Avenue. A rush of friends wanted to know what I thought of prison company stocks. They were all in them, the brokers were pushing them, they were the “new hot thing” and they were anticipating delicious profits. I said get out, the pricings assumed incorrectly that piling people into prisons — the innocent and guilty alike — was like warehousing people in HUD housing. Sure enough, the stocks were to later plummet. But not until the Wall Street Journal ran a story about decorators using prison equipment to do bathrooms and kitchens on Park Avenue and Esquire ran a fashion layout in front of a series of jail cells. To this day, I wonder how many of the people I spoke to that evening had bought Cornell Corrections stock from Dillon Read.

I came back to Washington, D.C. feeling that the world had indeed gone mad. Everywhere I turned I saw people who seemed quite happy to make money doing things that drained and liquidated our permanent infrastructure and productivity as a people and a nation. Our financial system had become a complex mechanism that allowed us to profitably disassociate from the sources of our cash and concrete reality.

After several conversations with my attorneys, I realized that the efforts to frame us had failed and now those involved had been left with a bit of a mess as we were turning in the court affidavits that documented intentional falsification and suppression of evidence. My assessment was that DOJ would be willing to drop everything if we simply let them keep all of The Hamilton Securities Group’s money. Whatever the urgent thrust had been, it was over. Was it because Dillon had now cashed out all of their money? Was it because all of the software tools and databases were effectively suppressed and would not lead millions of Americans to connect mortgage fraud with the Dark Alliance story? Was it because the covert cash spigot had been turned on and $59 billion was pouring out of HUD to feed the hungry beast the appetizer followed by a main course of $3.3 trillion missing from the Pentagon? Was it because, with honest people forced out and the bureaucracy properly terrorized, the housing bubble was now being fueled with explosive federal credit from FHA, Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac? Or was it a combination? More than anything, there had been a very intense and personal desire to see me in prison. It had failed. I made a decision that I was not going to simply walk away. I was going to get to the bottom of what happened.

What communities in America and worldwide most need is the truth. We need the ability to know whom we can trust and who we cannot trust. We need to know how to build a life, a family, a small company, and retirement savings and be able to protect them from corruption. We need to generate an income that builds up our wealth and equity, rather than a subsidy that keeps us going while our equity slowly drains out of our savings and our communities. Any successful explorer will tell you that all the resources in the world are of little use if you have a bad map and as a result end up naked to the elements.

Catherine Austin Fitts’ home, Fraser Stables, a converted carriage house and stables in downtown Washington, D.C. was sold to help defray the expenses of litigation and escape ongoing physical harassment and surveillance. (Photos courtesy Catherine Austin Fitts)

The first step was to understand organized crime — a topic that I had never been interested in. I called an organization that sold tapes by researchers on government corruption and narcotics trafficking and bought the tapes he recommended. So began a journey of reading and watching thousands of books and videos and networking with researchers globally.

Later that year, I published an article about the potential connection between the Dark Alliance allegations and the efforts to suppress our transparency tools and what that may imply regarding the possible use of HUD mortgages and mortgage fraud by these same networks. Right after the article was published on May 22, 1999 with copies delivered to the Intelligence Committee subscribers, Congress suddenly held closed hearings on Volume II of the CIA Inspector General’s reports, taking testimony in secret from DOJ Inspector General Michael Bromwich and CIA Inspector General Britt Snider.[87]

It was clear where things were going by that summer. In June of 1999, Richard Grasso, Chairman of the New York stock exchange, went to Colombia to visit a Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) Commander to encourage him to reinvest in the U.S. financial system. At the time of his visit, the General Accounting Office reported on FARC’s growing influence in the Colombian cocaine market.[88]

As I learned more about the black budget and covert cash flows at work in our economy, I also learned more about their history. I began to connect more of the dots to my personal history and that of my family, friends and neighbors. I realized that the viciousness of the current attack could relate not just to my work at Hamilton but to problems that my family had dealing with similar, if not the same, people long ago. [88.5] It only served to reinforce the wisdom of my decision to pursue the litigation and get to the bottom of what was happening and why. In the famous words of George Santayana, “those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” I was to spend many years resolving the litigation and building new networks that I needed to found and grow my investment advisory company — helping to preserve and grow family wealth in a world increasingly defined by financial and political corruption.

| Next Chapter |