I left the Bush Administration in 1990, persuaded that digital technology and the Internet could be used by entrepreneurs to create new wealth in an investment model that created alignment between global investors and the land, environment and people. If we financed places with equity instead of debt, we could create a way for global investors to profit from reducing consumption of scarce resources, integrating new technology into our infrastructure, healing the environment and improving my rule of thumb for the health of a community — the Popsicle Index.[52] The Popsicle Index is the percentage of people in a place who believe a child can leave their home and go to the nearest place to buy a popsicle or snack and come home alone safely.[53]

When I was a little girl growing up in West Philadelphia, the Popsicle Index was close to 100%. The Dow Jones was 150. Today, in my old neighborhood the Popsicle Index has fallen about 90% to 10% while the Dow Jones has risen more than sixty times to over 10,000. In short, we have a win-lose relationship between investors and communities. In addition, we also have a win-lose relationship between government and communities. For more than fifty years we have had steadily rising government budgets for programs and enforcement (often justified on the theory that they will make the Popsicle Index go up) and a steadily falling Popsicle Index.

The Hamilton Securities Group offices won an award from the American Institute of Architects for Advanced Technology Facility Design.

(Photo courtesy The Hamilton Securities Group)

In 1991, at the same time that Dillon was bankrolling the Cornell Corrections start-up, I started an investment bank and financial software firm in Washington called The Hamilton Securities Group. Hamilton was named after Alexander Hamilton, one of the key drafters of the U.S. Constitution. While I served as Assistant Secretary of Housing-FHA Commissioner at HUD, I tried on numerous occasions to persuade Secretary of HUD Jack Kemp and his staff not to propose new policies that would result in the abrogation of government contracts or contractual obligations with respect to financial assets. I had a deputy who always reminded me that Alexander Hamilton had gone through a similar process of ensuring that the government did not illegally abrogate its obligations and debts when he was the first Secretary of the Treasury of the United States — and that Hamilton had always prevailed. Numerous Alexander Hamilton quotes became part of our way of cheering ourselves up in the midst of cleaning up nauseating levels of corruption. Sayings like “A promise must never be broken.”

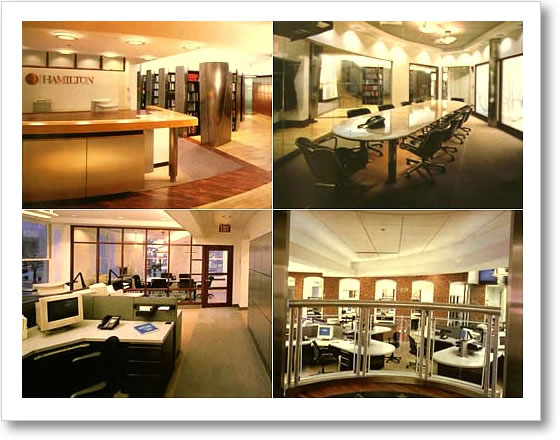

In 1995, Hamilton Securities integrated telephone and computer systems in an open office design. Whether at a desk, in a conference room or in the kitchen, Hamiltonians and network members — many educated and experienced in information technology — could access state of the art technology, software tools and a T1 Internet line.

(Photos courtesy The Hamilton Securities Group)

One of The Hamilton Securities Group’s goals was to map out how the flows of money worked in the U.S. and create software tools that would make this information accessible to communities. We believed that the way to re-engineer government was for citizens to have access to the information about the sources and uses of taxes and government spending and financing in their communities, and to participate in the process of making sure that these investments were managed to restore our neighborhoods to a “Popsicle Index” of 100%. Transparency is essential for private markets to work and for government investment to be economically productive, accountable to those who fund it and managed according to the laws that are supposed to govern such investment. Otherwise, we will veer toward subsidizing private interests that are powerful politically or forceful, including through dirty tricks and economic warfare, as opposed to those that are productive.

After I started The Hamilton Securities Group, I was approached by Nick Brady, still Secretary of Treasury, to serve as a Governor of the Federal Reserve. When I declined, John Sununu, then White House Chief of Staff, had me appointed to the board of Sallie Mae, the corporation that helps to provide financing for student loans. While on the board of Sallie Mae, I was taken aside by the Chairman who explained that it was essential for me to ask Nick to sponsor me for membership in the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). When I said that this was not something I felt comfortable doing, he said, quite alarmed in a generous and caring manner, “You don’t understand, if you don’t join the Council, you will be out for good.”

I did not join the CFR and in retrospect — after years of watching how the CFR and its members operate — believe I made a sound decision. My dream was to find solutions. That required getting in the trenches to prototype money maps, tools and transactions. Prototyping of this type requires high degrees of trust with diverse networks — in communities and financial markets alike. Some of these networks would not welcome a central banker or members of organizations like the CFR that provide the intellectual smokescreen for the centralization of financial data and flows and economic and political power.

Over time I was increasingly shocked by the speed and ease with which many intelligent and seemingly competent members of the CFR appeared to eagerly justify policies and actions that supported growing corruption. The regularity with which many CFR members would protect insiders from accountability regarding another appalling fraud surprised even me. Many of them seemed delighted with the advantages of being an insider while being entirely indifferent to the extraordinary cost to all citizens of having our lives, health and resources drained to increase insider wealth in a manner that violated the most basic principles of fiduciary obligation and respect for the law. In short, the CFR was operating in a win-lose economic paradigm that centralized economic and political power. I was trying to find a way for us to shift to a win-win economic paradigm that was — by its nature — decentralizing.

Catherine’s home in Woodley Place, Washington, D.C. was sold to help finance Hamilton Securities.

(Photos courtesy Catherine Austin Fitts)

The Hamilton Securities Group was financed with the money I made as a partner of Dillon Read and the sale of my home in Washington and then financed internally with reinvested profits from operations. Several years after starting, we won a contract by competitive bid to serve as the lead financial advisor to the Federal Housing Administration FHA at HUD. As a result, I had the opportunity to serve the Clinton Administration in the capacity of President of The Hamilton Securities Group in addition to having served as Assistant Secretary of Housing-FHA Commissioner in the first Bush Administration.[54]

One of our assignments for HUD was serving as lead financial advisor for $10 billion of mortgage loan sale auctions. Using online design books[55] and our own analytic software tools as well as bidding technology from Bell Laboratories we adapted for financial applications, we were able to significantly increase HUD’s recovery performance on defaulted mortgages, generating $2.2 billion of savings for the FHA Mutual Mortgage Insurance and General Insurance Funds.

While we plowed all of our profits back into the expenses of building databases and software tools and into banking a community-based data servicing company, we were still profitable, generating $16 million of fee revenues and $2.3 million of net income in 1995.[56]

While the loan sales were a great success for taxpayers, homeowners and communities, it turned out that they were a significant threat to the traditional interests that fed at the trough of HUD programs, contracts and related FHA mortgage and Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac mortgage securities operations.

For example, if you illuminated the sources and uses of government resources on a neighborhood by neighborhood basis, you would see that government monies were spent in ways that created fat stock market and personal profits for insiders at the expense of more productive outsiders who are providing most of the tax and other resources used. Insiders could include big developers and property management companies that specialized in HUD-subsidized properties like then Harvard Endowment-owned National Housing Partners (NHP) and their affiliated mortgage banking operations like NHP’s Washington Mortgage (WMF), or for investment bankers like Dillon Read or Stephens, Inc. who issued municipal housing bonds for agencies like the Arkansas Development and Finance Agency (See “Narco Dollars in the 1980s—Mena Arkansas” above). When I suggested to the head of HUD’s Hope VI public housing construction program during the Clinton Administration that she could spend $50,000 per home to rehab single family homes owned by FHA rather than spending $250,000 to create one new public housing apartment in the same community, she got frustrated and said “How would we generate fees for our friends?”

Our efforts at The Hamilton Securities Group to help HUD achieve maximum return on the sale of its defaulted mortgage assets coincided with a widespread process of “privatization” in which assets were, in fact, being transferred out of governments worldwide at significantly below market value in a manner providing extraordinary windfall profits, capital gains and financial equity to private corporations and investors. In addition, government functions were being outsourced at prices way above what should have been market price or government costs — again stripping governmental and community resources in a manner that subsidized private interests. The financial equity gained by private interests was often the result of financial, human, environmental and living equity stripped and stolen from communities — often without communities being able to understand what had happened or to clearly identify their loss. This is why I now refer to privatization as “piratization.”

One of the consequences was to steadily increase the political power of companies and investors who were increasingly dependent on lucrative back door subsidies — thus lowering overall social and economic productivity. Hence, the doubling of FHA’s mortgage recovery rates from 35% to 70-90% ran counter to global trends and ruffled feathers. FHA, with Hamilton’s help, was requiring investors like Harvard Endowment to pay full price for assets while it appeared that they and investors like them were engineering progressively deeper and deeper windfall discount prices as part of government privatization programs elsewhere in the U.S. and globally. A Federal False Claims Act lawsuit against Harvard and journalist coverage regarding their role as a USAID government contractor in Russia illuminated the extent of the windfall profits that they and members of their networks were able to engineer at the expense of the Russian people, investors and the American people.[57]A criticism that I now have that I did not understand at the time was that even efficiently and honestly executed privatization transactions such as the HUD loan sales policies which insist on open competition at the highest price run the risk of advantaging players who were the most successful at laundering money for the “black budget.” All solutions to this problem bring us back to the importance of place-based transparency of government resources and the importance of investing in the equity of small businesses and small farms.

Things took an even darker turn when we started Edgewood Technology Services, a data servicing company in a largely African-American residential community in Washington, D.C.[58] Our investment in Edgewood gave us the ability to develop a skilled dedicated workforce that could help us build much more powerful databases and software tools. It also helped us understand the investment opportunity to train people working at minimum wage jobs or living on subsidies to develop more marketable skills and earning power by doing financial data servicing and software development.

From the financial information that emerged from our portfolio strategy work for HUD and from our investment in Edgewood, we discovered that it was less expensive to train people to do these jobs than to fund their living on government subsidies indefinitely, let alone going to prison. For example, a woman with two children living in subsidized housing in Washington, D.C. on welfare and food stamps cost the government $35-55,000 or more. In 1996, the General Accounting Office (GAO) published a study showing that on average total annual expenditures for federal, state and local prisoners was over $150,000 per prisoner. Presumably this included all overhead and capital costs but did not include the costs of supporting minor children of such prisoners. If government funded the care of her two children while she was in prison, those costs would be in addition.

What we found at Edgewood was that there was a portion of the work force that, due to obligations to children and elderly parents, was not able to commute. Some of these people could be a productive work force working near their home and developing computer and software skills at their own pace. If training was combined with the creation of jobs, the economics of training people to do these jobs were sustainable and with proper screening and management could be profitable for the private sector. The potential savings to the public sector was astonishing — not to mention the potential improvement in quality of life for cities, suburbs and rural communities. With government leadership and large corporations actively working to move jobs abroad, people in all areas of the U.S. would need these kinds of new skills and jobs. Moreover, small businesses would need access to the kinds of venture capital and financial equity we were proposing to invest in community venture capital. That meant that communities needed to circulate more deposits and savings internally rather than depositing and investing their funds in large banks and corporations that used those funds to win local market share away from small businesses and farms.

During this period, The Hamilton Securities Group helped HUD develop a program to permit owners of HUD-subsidized projects to treat some of the costs of community learning centers as “allowable costs” that could be funded from property cash flows. This allowed apartment building operations in communities experiencing welfare reform, cutbacks in domestic programs and unemployment from jobs moving abroad to provide facilities and programs that could help residents improve their ability to generate income. It encouraged linkages between private real estate managers and community colleges and other organizations committed to helping people learn new skills.

As I traveled and researched around the country, it became apparent that data servicing jobs like those we were prototyping at Edgewood were highly competitive with jobs in the illegal economy. In other words, data servicing jobs paying $8-10 per hour and offering health care benefits and the opportunity to improve skills had the potential to attract a surprising number of people away from dealing drugs, prostitution and other street crime. The Hamilton Securities Group’s primary competition for the younger multi-racial portion of this work force appeared to be organized crime and the industries dependent on the continuation of organized crime activities — including enforcement and private prisons.

Meanwhile, The Hamilton Securities Group’s growing software and database infrastructure about public and private resource flows in communities indicated that the vast majority of government subsidies were either not necessary or not economic — whether welfare and HUD subsidies or prisons and the huge and growing infrastructure of community and social development and private real estate and government contractors that they supported. There was a much more economic way for government to reduce domestic subsidies and crime. Billions of dollars of government investment had a negative return on investment. We were paying millions of people — whether on welfare or government contracts or HUD property subsidies — to do things that were not productive. Change those expenditures to a positive return on investment, and extraordinary improvements in productivity were possible. There was much work needed to be done that warranted investment — from repairing our infrastructure to rebuilding communities. As part of the potential opportunities, with both the private sector and federal government predicting very significant increases in the need for data servicing support and other jobs that could be outsourced through telecommunications, there appeared to be a significant opportunity. We shared our data and results with HUD, The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Congress and the Office of Management and Budget at the White House, and with leaders within the real estate and community development industries.

The initial response was very positive from a number of quarters, particularly those people most concerned with the growing federal debt and issues of productivity. I will never forget one of our meetings with a senior White House official. We showed him our initial estimates of the savings that were possible from potential reduced subsidy expenditures as well as lower default rates on federal mortgage and loan programs as a result of increased employment and income in low and moderate communities. He was ecstatic about the potential to save billions while reducing poverty — all recently made possible by new technology. He and many other government officials — when they saw the initial estimates emerging from the loan sales and our aggregates of the extraordinary amounts of federal monies being wasted by place — realized the potential when a negative financial return on investment is reengineered to a positive return on investment in a place.

Private investment leaders were also enthusiastic. During one presentation, the head of portfolio strategy for one large corporate fund said with astonishment, “This is terrific. We can save the country and make a fortune doing it.” Making a fortune was a good thing. One of our biggest concerns was achieving a sufficient investment performance on pension fund capital to ensure that retirement benefits were adequately funded. Hamilton was proposing a financial model that would also help fund retirement obligations as a result of pension funds profiting from the wealth created by reducing poverty.

Others were not so positive, including special interests whose business had become managing “the poor” and who would be out of a business if new tools and opportunities were to significantly decrease the number of people who were poor. Many of these were traditionally powerful Democratic constituencies, including private for-profits, foundations, universities and not-for-profit agencies that had built up a significant infrastructure servicing and supporting programs to house, feed and supervise poor people. If people were no longer poor, what was their purpose? When we made a presentation to a group of leading foundations, in partnership with a Los Angeles entertainment company interested in using entertainment skills to make training fun, the head of low-income programs at Fannie Mae told me that it was the most depressing presentation he had ever seen. It implied that the poor did not need his help — that his life and work had no meaning. It appeared he did not want to end poverty. His personal meaning was derived from poverty continuing, if not growing. Real estate interests that were hoping to gentrify neighborhoods as a result of welfare reform were also not pleased. They would make more money turning over populations rather than helping the current population improve without moving. Their allies were enforcement teams like the HUD OIG that won funding and generated revenues from helping to get one group out, so another group could be moved in.

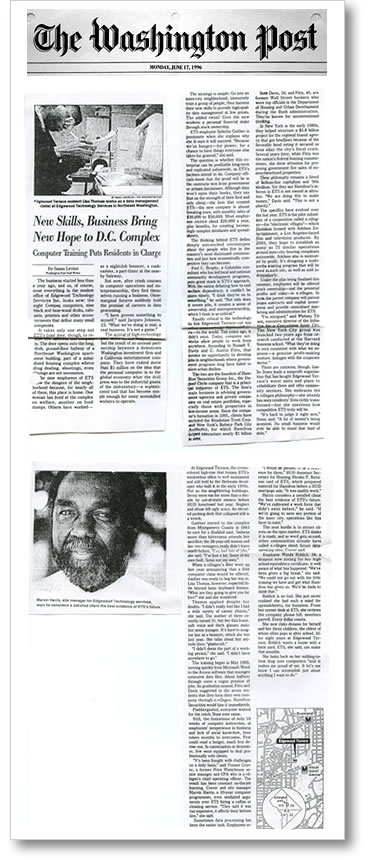

One HUD official told Catherine that when she saw this June 1996 Washington Post article about Edgewood Technology Services, the HUD Inspector General said, “That’s it, I am going to get her [referring to Catherine.]”

We were warned that the HUD Inspector General’s office had a very negative response to the “neighborhood networks” model of community learning centers, with one of the enforcement team members referring to such efforts as “computers for niggers.” Essentially, the vision we were proposing was in competition with their enforcement business, which consisted of dropping 200 person “swat” teams into a neighborhood to round up and arrest lots of young people who were in the wrong place at the wrong time and could not afford an attorney. This required a fundamentally different approach and philosophy. One model proposed helping the people in a place improve. The other proposed rounding them up and pushing them out so that new people could be moved in.

The highly successful HUD loan sales had also run into a problem with the staff of the HUD Inspector General’s Office. According to HUD staff, the HUD OIG staff wanted the HUD loan sale staff to withdraw loans from sale portfolios so they could pursue civil money penalties against the building owners. If the loans were sold, it would be better for the FHA fund and for building residents and the surrounding communities. However, it would make less money for the “Sheriff of Nottingham” business in HUD OIG. The IG and General Counsel staff were apparently indifferent to overall best interests of the government on a government wide basis let alone taxpayers and communities.

Years later, when HUD Inspector General Susan Gaffney was asked during a deposition what the recovery rates were on HUD’s defaulted mortgage portfolio before, during and after the loan sale program that The Hamilton Securities Group pioneered, she said she had no idea. Her attitude suggested that this was not an important piece of information. Which suggests that she found something that had billions of dollars of impact on the FHA Funds each year to be of no interest. The focus in federal enforcement was on activities that made money and garnered funding support and headlines directly for the enforcement teams. This “for-profit ” philosophy was surprisingly blatant. I was reminded of the Congressman who jumped up from dinner to cast his vote in appropriations committee and as he rushed off said to me, “Let’s face it, honey, I’m only here to protect my shit.”

In late 1995, The Hamilton Securities Group began work on Community Wizard, a software tool designed to facilitate community Internet access to all public data and some private data on local resource use, including federal tax, expenditures and credit data. The initial response to the tool from Congress, HUD and our technology networks was astonishing. People were ecstatic to realize that they did not have to continue to live and work in the dark financially. It was a relatively easy thing for new software tools to help people learn about the flow of money and resources in their community. Additional software tool development also resulted in numerous tools to analyze subsidized housing in a place-based context, including detailed pricing tools that combined significant databases on government rules and regulations with all of our pricing data from the various loan sales, with databases about mortgage, municipal and stock market financing of homebuilding and home ownership. Such tools would allow people to take a positive and proactive role in insuring that government resources were well used. Such tools would allow investors to improve the performance of local investment — particularly venture and equity investment in small businesses and farms.

Community Wizard Brochure

(Photo courtesy The Hamilton Securities Group)

There was only one problem. If communities had easy access to this data, the pro-centralization team of Washington and Wall Street would be in trouble. Everything from HUD real estate companies to private prisons would be shown to make no economic sense — other than to generate private profits and capital gains for insiders. And billions of government contracts, subsidies and financing would be shown to make no economic sense — other than to generate private profits and capital gains for insiders. Indeed, communities were better off without many of these activities and funding. Through our software, private citizens would see the cost of decades of accumulated “fees for our friends.”

A case in point was a meeting I had with a former partner of Dillon Read who I had hoped to recruit to Hamilton in 1996. He came to our offices and during my presentation of our plans for community venture, told me that the situation was hopeless and that our tools would make no difference. I powered up Community Wizard and our software tools on the monitors and asked him where he lived. He said “Bronxville, New York.” I had one of my team print out from our databases a list of federal expenditures in his neighborhood. When he saw the first item, he exploded with rage, “$4 million last year for flood insurance? That is ridiculous. That is corrupt!” $4 million of flood insurance sounded pretty innocent to me and I said, “why is that corrupt?” He said, “Bronxville is on a hill. I have lived in Bronxville for many years and I have never seen or heard of a flood.” It is typical that someone with years of experience in a place can spot potential waste and reengineering opportunities much faster when presented with detailed government financial information than someone who does not know the place.

As the former Dillon Read partner started to read through the details of the annual expenditures, he became more and more upset. The next day we were scheduled to speak by conference call after he returned to New York. I called and called at the appointed time but the line was busy. When I finally got through, he said he had been on the line with the Deputy Mayor of Bronxville for hours going through the data we had provided him. He said, “All this corruption is going to stop.” I said, “I thought you said it was hopeless.” And then he said something to the effect of “that was until I got the numbers for my neighborhood.” He understood that the corruption is funded one neighborhood at a time. If each neighborhood cuts off or reengineers the flow of wasteful or corrupt government funds, the situation can transform in a significant way nationally and globally. You have to cut off the money to the bad guys at the root. And he had realized how much money per person was being wasted when he saw the waste on a human scale where he could both see how the resources could be properly used and could do something about it.

This was, however, before we even addressed the question: “Who was bringing in narcotics and where was all the money from the trafficking and other illegal activities going?” If enough people stopped dealing drugs and taking drugs, then who needed more prisons and all these enforcement agencies and War on Drugs contractors? And how did all of this connect with the stock market and the mortgage markets and the fraud in those markets?

Ask and answer those questions — as communities would now be able to start to do with tools like Community Wizard and our tools — and much Iran-Contra style narcotics trafficking, the private prison industry and the “Sheriff of Nottingham-style” enforcement programs so in vogue at the White House, DOJ and HUD OIG might just be dead in the water. Unfortunately, that might have profound implications for the existing financial market as many corporate and government securities depended on the continued flow of wasted government expenditures.

The Map of South Central Los Angeles, California

(Map courtesy The Hamilton Securities Group)

As part of our efforts, we started to publish maps on the Internet of defaulted HUD mortgages in places with significant defaulted mortgage portfolios and to encourage HUD to offer place-based sales that would allow bidders to bid on different types of HUD-related mortgages and properties in one place. If successful, it would permit us to also create bids that optimized total government performance in a particular place — including assets from other agencies as well as contracts, subsidies and services.

One of the maps we put up in the spring of 1996 showed the properties which were financed with defaulted HUD single-family mortgages in South Central Los Angeles, California. The map showed significant HUD defaults and losses in the same area as the crack cocaine epidemic described by Gary Webb in Dark Alliance. Such heavy mortgage default patterns are symptoms of a systemic and very expensive problem — including systemic fraud. This could occur, for example, in situations such as those in which mortgages were being used to finance homes above market prices with inflated appraisals (one of the patterns of HUD fraud documented by the The Sopranos TV show) or where defaulted mortgages or foreclosed properties were being passed back to private parties at below market values, or where these types of mortgage fraud were supporting mortgage securities (such as those issued by Ginnie Mae, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae) that did not have real collateral behind them. This is the type of mortgage fraud that launders profits in a way that can multiply them by many times. Los Angeles was also the area with the largest flow of activities in the Department of Justice’s Asset Forfeiture Fund. Whether drug arrests and incarcerations, legal support for HUD foreclosures and enforcement or asset seizures and forfeitures — these maps were illuminating areas that were big business for “Sheriff of Nottingham-style” operations.

The Map of Washington D.C.

(Map courtesy The Hamilton Securities Group)

The Map of New Orleans

(Map courtesy The Hamilton Securities Group)

| Next Chapter |